Shipbuilding in Baltimore

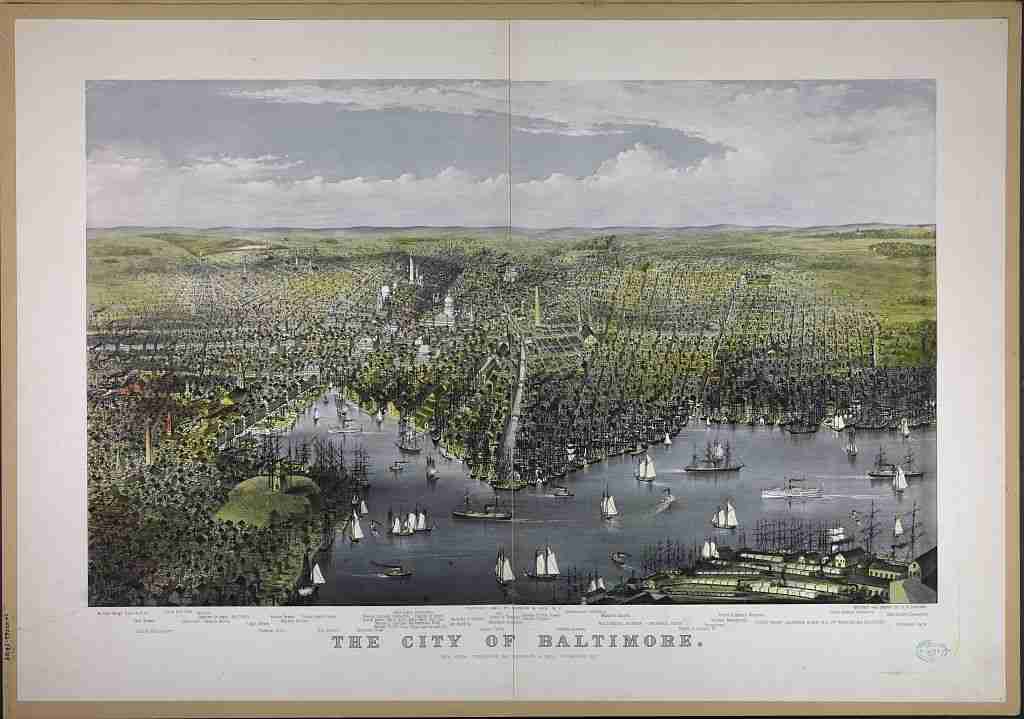

Baltimore was a thriving commercial trade port in the 18th century. Most shipping from Baltimore, until the Industrial Revolution, was overseas trade of tobacco, grains, and cotton.

The busy port created a high demand for ships, and soon Baltimore’s first shipyards were dotting the waterfront along Fells Point. These first ships were wood-hulled sailing ships.

Shipbuilding expanded greatly during the American Revolution, and especially after 1790 when shipbuilders developed vessels like the clipper and schooner. Sleek and fast, these ships were in great demand for trading, wartime use, and by privateers.

With the development of steam-powered ships in the 1800’s, ship captains were finally able to control the speed and direction of the vessels they operated, making water travel and trade more dependable. By the 1830’s, Baltimore shipyards were building steamboats and steamships, including steam-powered tugboats.

Before the introduction of tugboats, boats leaving and entering ports were completely at the mercy of tides and weather conditions. An integral part of directing port traffic, tugboats have contributed significantly to the growth of the Port of Baltimore and the development of the shipping industry throughout the world.

The City of Baltimore / sketched and drawn by C.R. Parsons. (ca. 1880) Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

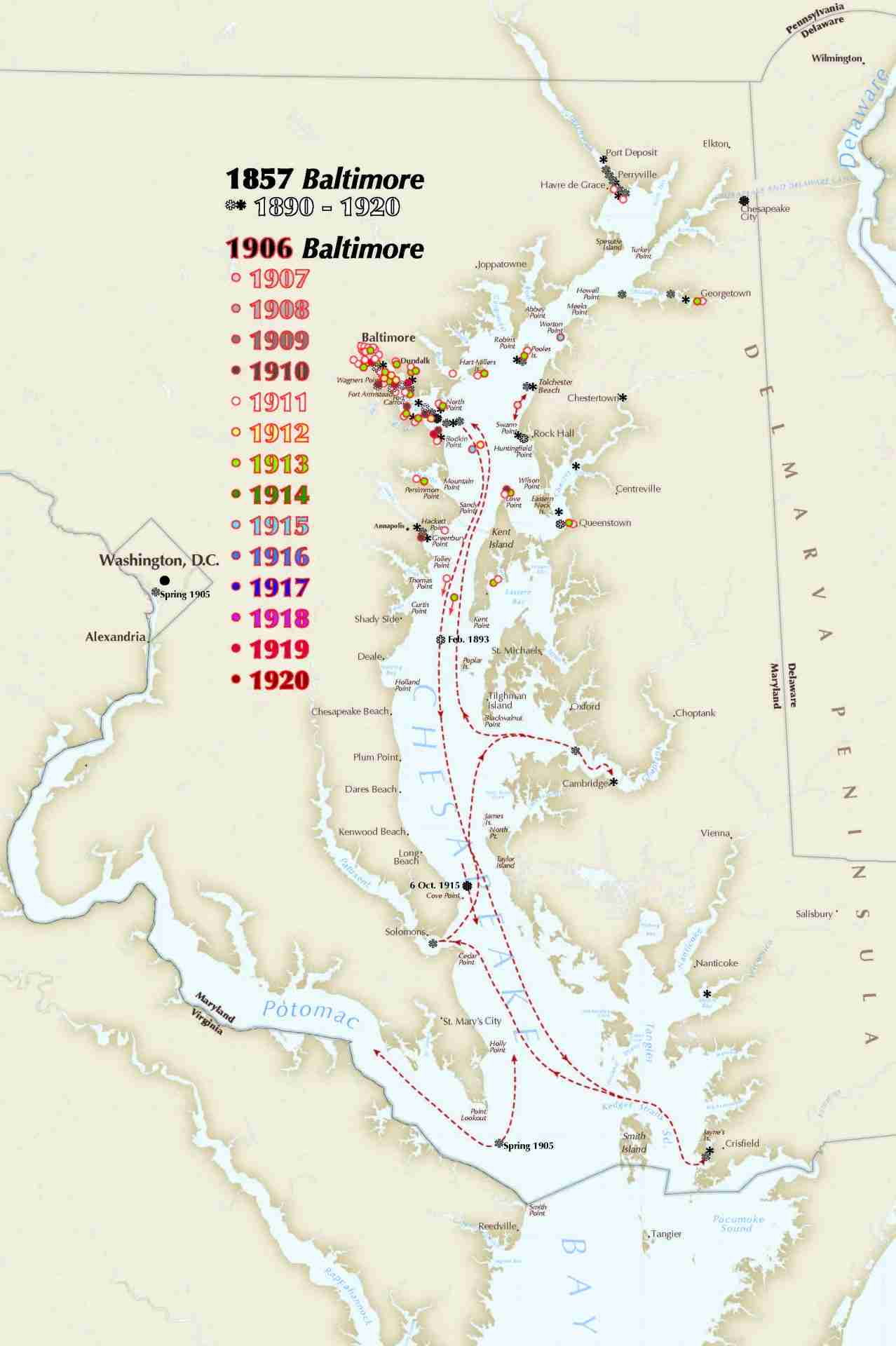

Steam Tug Baltimore 1857 and 1906

The original steam tug Baltimore was built in 1857, and was the first iron-hulled tugboat built in Baltimore by the steam boiler and engine builder, Murray & Hazelhurst. Their location was near the current site of the Inner Harbor’s Science Center.

The Baltimore Museum of Industry’s steam tug, S.T. Baltimore, is a good example of a steam work boat of the early twentieth century. The Skinner Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Company launched the tug “Baltimore” in 1906. Until 1963, she was used to move pile drivers and barges, break ice, and tour special port visitors.

This second Baltimore tug sank in 1979 in fifteen feet of water and was subsequently donated to the Baltimore Museum of Industry who raised her in 1981. She is the oldest steam-powered tugboat in the United States, and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1993.

The crew of the S.T. Baltimore is currently looking for some volunteers with experience in carpentry for fall 2022. Interested in volunteering? Fill out the form below and we’ll be in touch.

[button url=”#reservation” size=”big” color=”color1″ full_width=”no” align=”left”]Contact Me About Volunteering![/button]

The first steam tug Baltimore was built in 1857. Her hull was sheet iron, the first in the port.

The Skinner Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Company launched the tug “Baltimore” in 1906. Visit the Baltimore Museum of Industry to see her today, the oldest steam-powered tugboat in the United States!

A typical morning on the S.T. Baltimore

Originally, the tug Baltimore had a four-man crew, consisting of a licensed captain, a licensed chief engineer, a deck hand, and a fireman. A typical morning on the S.T. Baltimore would start with the fireman arriving at 6 a. m.

The fireman puts his soup on the stove and stows his bag lunch in the ice chest on the upper deck (each crew member brings his own kettle of soup and his own sack containing a full breakfast and a sandwich for lunch). The fireman lights the lantern, goes down into the fo’c’sle to change his clothes and then into the boiler room. The night before, the fireman had banked the fires. Now he breaks up the fires, pulls out the clinkers (big chunks of coal), and places them on the steel deck to hose them down. He is ready to raise the steam that is as low as 70-80 lb. in the early morning. It will take him 1.5 hours to fully raise the steam.

One hour before sailing time the deck hand arrives, changes his clothes in the fo’c’sle and puts away his lunch and soup. By this time, the lights and steam generator are already operating. The deck hand takes the water hoses out of the forward and after tanks where he placed them the night before. His job is to supply all of the water needed that day. He goes to the watchman’s shack to get the morning ice (50 lb.), which was delivered at 6 a.m. He puts the ice in the ice chest.

A half hour before sailing time, the chief engineer arrives, changes his clothes in the fo’c’sle and puts away his lunch and soup. He opens the steam stop for the main engine, and works the engine ahead and astern to work the water out of the engine in order to raise a vacuum. This allows the engine to turn slowly ahead at about 25 rpm.

The captain also arrives a half hour before sailing time, bringing with him the morning orders that he picked up from the Harbor Board the night before. The captain does not change his clothes on board. He comes to work dressed in khaki or blue trousers, a white shirt, dark tie, blue blazer and his captain’s cap. He proceeds to check over the vessel, looking to see that there is water and enough coal on board to make steam, kerosene for the emergency lighting system, and lubricating oil for the main engine.

Then the Baltimore is on its way.

Baltimore’s destinations map

Visit the BMI’s Connection Factory to connect with stories that show how education, exhibitions, and partnerships strengthen our community.