Interview by Deb Weiner

Kathy Garrison started working at Bethlehem Steel in 1976, not long after a consent decree required the company to stop discriminating against women and minorities. She chaired the Women of Steel group from 2004 to 2012, when the plant shut down. Here are edited excerpts from her recent interview with BSLP consultant Deborah Weiner.

To discover more about Bethlehem Steel’s Women of Steel, see the free outdoor exhibit currently on display at the BMI.

I was born in Edgemere, right outside of Bethlehem Steel in Sparrows Point. You can see the steel mill from the back of our house. Almost all of the neighbors were steel workers, and their wives were homemakers. That was the way of life. Some of the women worked, but most were homemakers and took care of the family.

Women of Steel members present a check for $3,000 to representatives of the Bea Gaddy Fund, 2007. From left: Kathy Garrison, Mary K. Hamilton, Gail Fleming, Bea Gaddy rep., Sharon Pritchard, Bea Gaddy rep., Vanessa Smith. Courtesy of Kathy Garrison.

My father passed away when I was a baby. My mother worked in the Bethlehem main office. She worked for 42 years down there. She made decent money, but she didn’t make the kind of money that some of the people in the mills did. I got married at 16, which wasn’t unusual back then. My husband started in the tin mill around 1969. Then he went to Vietnam, came back, and we got married in ’74.

I started in the mill in ’76. My mother came home from work one day, and she said, “They’re going to be hiring, and they’re going to hire women.” She always told me, “You don’t have to be the cheerleader, you can play the game. Don’t limit yourself by being a woman.” I just never could understand why people expected less of you because you’re a woman.

I said, “Well I could work down there.” Usually they would hire hundreds and hundreds at a time. People would go down and stand in line. The line would wrap around the building, you know? Because it was that many people that wanted to work there. It was a chance for a really good, middle class lifestyle. Decent money, good benefits.

My brother was just graduating from high school. He was getting ready to go down there. I said, “I’m going to go with you.” My husband didn’t really like the idea at all. They laughed at me and said, “You could never work down there.” I said, “Yes, I could. Yes, I could.” So I went down with my brother to put an application in. We stood in line for hours and hours on end.

A week or so later, I got a letter saying I could come down and take the physical. That’s when my husband was like, “You’re not working down there. I don’t want you working down there.” And I said, “We could buy a house so much quicker, and we could…” We went back and forth, and finally, I’ll never forget it, he says to me, “Well, I tell you what. I’m going to let you work, but you’re going to have to keep up with the chores. And if it starts to cause problems, then you’re going to have to quit.” I was like, “Hm. All right, well, you know.”

I went down, and I took the physical and took the test. They told me I would be starting in the number four open hearth. When I told my husband that, he said, “Oh, no. That’s terrible, Kathy. Oh my God, that’s the most dangerous.” I was like, “What? I don’t know what an open hearth is.”

“It was an adjustment”

I started in the labor gang. They had never hired women into the [open hearth] department because it was very dangerous, very hot, very strenuous. They didn’t even have bathrooms for us. We had to go to the bathroom and have the foreman stand outside.

The women that I started with, they scattered us throughout. I was the only woman on my turn for a long time, and it was an adjustment. Because the guys, to be honest with you, they thought we were a novelty. I don’t think they really thought it would last, because who would want to work in a place like that? Especially a woman. You’d be walking along, and you’d hear somebody say, “Look, there goes one,” like you’re a bug or something.

I went into the pit in the number four open hearth. The pit was predominantly Black, because sadly enough, back in those days, the hardest jobs would go to the Black people. They used to call me little white girl. They were very, very accommodating, very nice. I think they thought, “She won’t be here long.” I think that they thought that of most of the women.

[Eventually Kathy worked in many different parts of the mill.] It was exciting, it really was. It wasn’t a boring job at all, there was always something. And the camaraderie… Once you earn the respect of the people that you work with, it’s almost like they’re your work family. You get to know their kids, you know what their kids look like. We were a very close-knit group for many, many, many years.Dealing with a man’s world

The steel mill was completely a man’s world. I developed quite a rough edge to me, just because that’s how I chose to deal with it. As it went on, they seen that I wasn’t going anywhere, and that we weren’t going anywhere, and that a lot of the women were bound and determined to make it.

It was a little bit of hostility. But I felt like I had been given the key to the boy’s clubhouse. That first paycheck they gave me, I was like, “This is mine? This is mine? This is all mine?” All’s I had to do was just shut my mouth, and do my job, and go home, and I would be just fine. I kind of put up with the comments and stuff like that, I just let it roll right off of me.

I heard things like, “You ought to be ashamed of yourself. You should be home with your baby.” I had a baby at the time, eight months old. My sister was taking care of her while I worked. I felt like I could do both, because my mom did. She worked and she raised us three kids, pretty much by herself, and she did a wonderful job. To me, that was normal.

I remember in the open hearth, this guy said to me one time, he says, “Isn’t this stuff too heavy for you?” I said, “Yeah, it’s heavy.” I said, “But you know what’s heavy? Heavy is four bags of groceries, a two-year-old on your hip, and a four-year-old, up three flights of steps. That’s heavy.”

The Women of Steel group

These Women of Steel buttons are preserved in the Baltimore City Archives. Photo courtesy of Bill Barry.

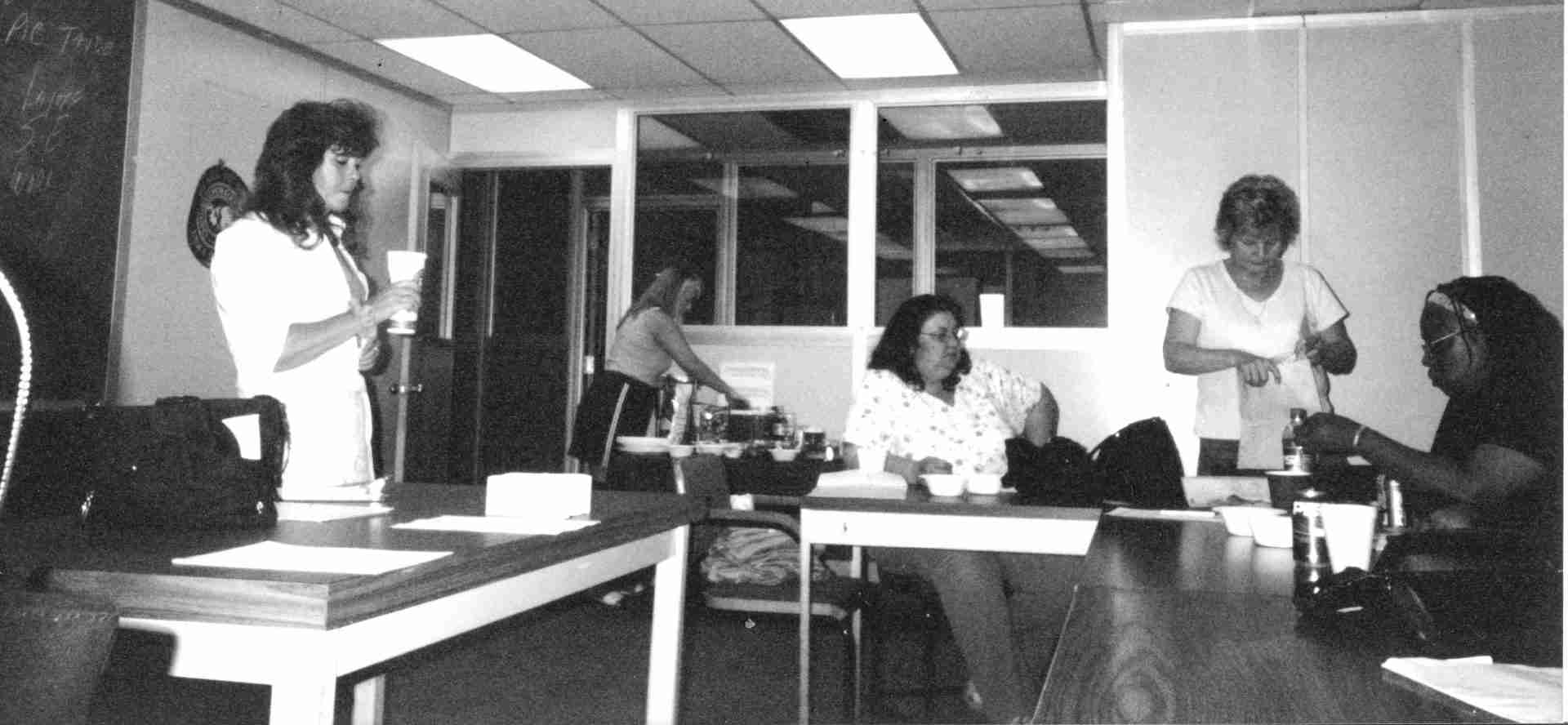

When you work with predominantly men, a lot of times, you don’t get as involved. Just simply because maybe you feel out of place. And a lot of women just disconnect. For the most part, they’re not hanging out at the bar with the guys after work, so they’re not getting a lot of the information, and their voices aren’t really being heard.

Women of Steel was set up to encourage women to get involved, and to take a seat at the table, and be a part. In 2004, they asked me if I would chair it. By that time, there were 220-some women throughout all the plants.

We networked with each other, and we did a lot of charity projects. We did a big Halloween dance every year. We would donate the money to House of Ruth, or to women’s issues, and stuff like that.

As it began to grow, women became more and more comfortable going to the union meetings and having a say in what goes on. Issues with work-life balance, and that sort of thing. Just getting involved, seeing what’s going on, knowing how to make changes if you want to make changes, and having a say-so.