Rita Hamlet began working on the ore dock at Bethlehem Steel shortly after the steel industry’s consent decree of 1974 opened more pathways to employment for women and African American workers. At Bethlehem Steel, Rita worked in many different places all while raising her five children. She sat down for an interview with labor historian Bill Barry in April 2019. In these edited excerpts, she recalls her nearly 30-year career at Sparrows Point.

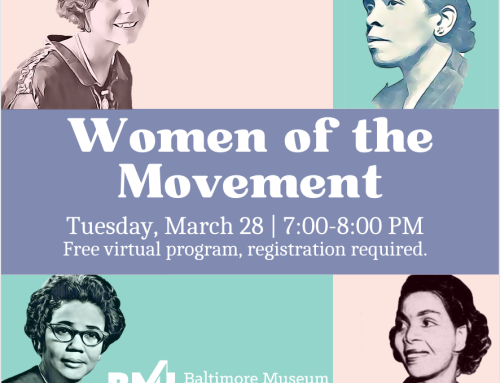

To discover more about Bethlehem Steel’s Women of Steel, see the free outdoor exhibit currently on display at the BMI.

“I wanted a man’s paycheck”

I took my brother and my cousin to fill out the application. I seen these two ladies and I say, “Miss, what was you all doing in there?” She said, “We’re filling out application.” I said, “They hire women?” She said, “They get ready to hire them.” I got out the car and went and filled out an application. Two weeks later I got hired.

They did tell me I had to gain 10 pounds. And I put rocks in my pocket and in my socks, and went back. And the man said, “In three weeks you’ve gained 7.4 pounds, so I know you’re gaining.” It was the rocks I put in my socks, in my pants pocket, down in my bra… The rocks gained the weight. I didn’t.

I was assigned to a place called the ore dock. Iron ore would come in [on ships]. We would have to put the rope around so the ships wouldn’t move, and guys would be on the ships pointing to me, “It’s a woman. It’s a woman.”

It was a little difficult at first because this guy said to me (and we were of the same race), “You wanted a man’s job.” The next time he told me [that], I say, “No, sir. I wanted a man’s paycheck. And since you wouldn’t give me yourn, I came and got my own.”

“You got to eat”

Let me tell you, when I first got hired, I didn’t like the job. I was scared. I got hired in May. I said, “Wait. I’m going to send my kids to summer camp. Then I’m going to quit.” They went to summer camp. Then I said, “Wait a minute. School getting ready start up. I need school clothes.” I said, “Wait a minute. Now it’s getting ready to be Christmas.” Then my kids grew up. I said, “Why are you still going to that God-forsaken job? The kids is grown.” I said, “Because you got to eat, dummy.” I said, “Oh, yeah, that’s right.” And that’s what made me keep going. Because guess what? The money. I made more money than people that I knew.

“That’s why you all hired me”

I thought I had to outwork the men. Because I was a woman, and they wasn’t going to keep me.

They told me that the government wrote that every 100 people that they hired, 25 had to be Black or women. So I knew when they hired me it was two checks instead of one. So I said, “That’s why you all hired me.”

When I first got there, some of the people wouldn’t even speak to you. And I couldn’t understand why because I come from a multi-race of people. My brother’s wife a white girl. I don’t care. Me and her’s friends. My daughter is married to a Jewish man. So I couldn’t understand them, but I made friends with this Caucasian lady, and she told me they were taught not to speak to Black people. Her nephew died. She said they didn’t have any money to bury him. I went all over Bethlehem Steel, taking up a collection, and I was nine dollars short of being $700. And I put the nine dollars to it, and she had $700. And then more people spoke to me.

[During down times] you’re waiting for the steel to come up, some of the white ladies would be reading books or doing something like polishing their fingernails. The boss came up to me one day, I was reading a book, “We don’t pay you to read a book.” I said, “Well, she’s reading her book,” and he just walked away. I would take the [manual on] how to operate the furnace and put the book in front of it so I would hide what I be doing.“The best thing that ever happened to me”

When I left the ore dock I went to the coke oven. The coke oven, it was hot and dangerous. It was mostly all black people except the supervisors. I was scared up there because there was a guy years ago. A belt broke, and the only thing you could see left of the man was his heels sticking up. I did not like the coke oven, because I just thought it was dangerous.

[Later] I went to a place called the ladle treatment station. When I went there, I was called a metallurgist. My job was, when the pot of hot molten lava came down, I would take a test. And whatever alloys was missing, it was my job to put the alloys in, make it hot as they wanted, and ship it out.To me, Bethlehem Steel was the best thing that ever happened to me, because I had to learn things. I had to grow up there. I had to do what was expected of me. I loved my job. Even now I miss it, and I miss the people that I worked with. I got close to the people because we built bonds.

[When Rita was a child] My grandfather would get up three o’clock in the morning and feed us breakfast, and say, “Shh,” then make us go back to bed. And then he would go in to Bethlehem Steel. [Later] I came home with my helmet on and my uniform, and he would hug me. He was so proud of me.

As a participant in BMI programs, Rita and others help pave the way for further change by sharing their inspirational stories with you.

Like Rita, you are a part of the Baltimore story. We depend on your continued support so that the BMI will always be a place where you can remember, connect, and be inspired.

The BMI needs your help NOW to preserve Baltimore’s industrial heritage. Whatever you choose to give, know that YOUR donation is essential to the BMI and to preserving and sharing Baltimore’s industrial story. DONATE NOW