By Clair Volkening

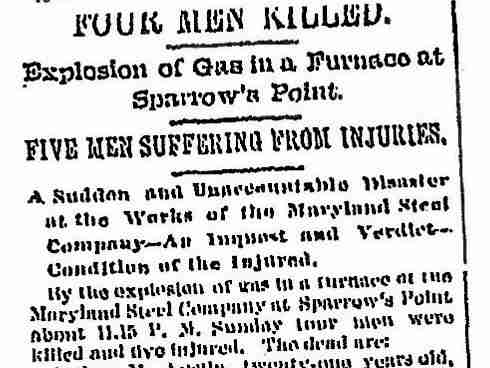

On Sunday, December 8, 1891, four men were killed and five suffered injuries after an explosion in blast furnace B at Sparrows Point.

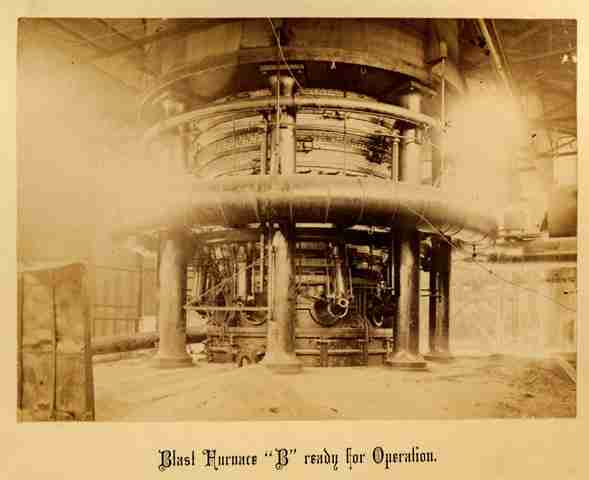

The night before the explosion, workers had begun “blowing out,” or shutting down, the furnace so that repairs could be made to the firebrick walls and the furnace pipes around the bosh, which is the hottest part of the furnace. The process was nearly finished when the explosion occurred.

When the “blow out” was almost over, Mr. David Baker, the superintendent for the furnace, thought everything was safe. However, when he went out onto the furnace roof he felt a draft of air from within the furnace and knew from experience that an explosion was coming.

Unfortunately, he did not believe that the explosion was going to be nearly as powerful as it was and was entirely unprepared. Baker and his assistants escaped serious injury even though they were standing on the furnace roof when the explosion happened and a piece of roof near them was blown off.

The men below were not so lucky. Because they were on the ground, there was nowhere for them to take shelter when flames roared out of the furnace. Hot bricks were hurled in all directions and the men were enveloped in fire.

An article in the Baltimore Sun detailed the deaths of those men: Arthur M. Austin, age 21, was “found about sixty feet away from the furnace, burnt to a crisp.” The blast killed him outright. He had been at Sparrows Point for only three months. George Braidwood, age 35, was badly burnt and suffered horribly before passing away early Monday morning. He left behind a widow. John Lynch, age 30, was found with a fractured skull and lived until 6:00 in the morning. Andrew Pugh, age unknown, had burns over half his body and severe head contusions when he died the next evening, leaving behind his wife and infant child.

Four other men, Augustus Bell, Thomas Miller, Washington Sapp, and W.T. Tubman suffered burns and head contusions but were not fatally injured. Although not named as one of the injured in any news articles, Baker is most likely the fifth injured worker.

What caused the explosion?

The Baltimore Sun called the accident a “sudden and unaccountable disaster.” Which forces the question: was it unaccountable, or could it have been prevented?

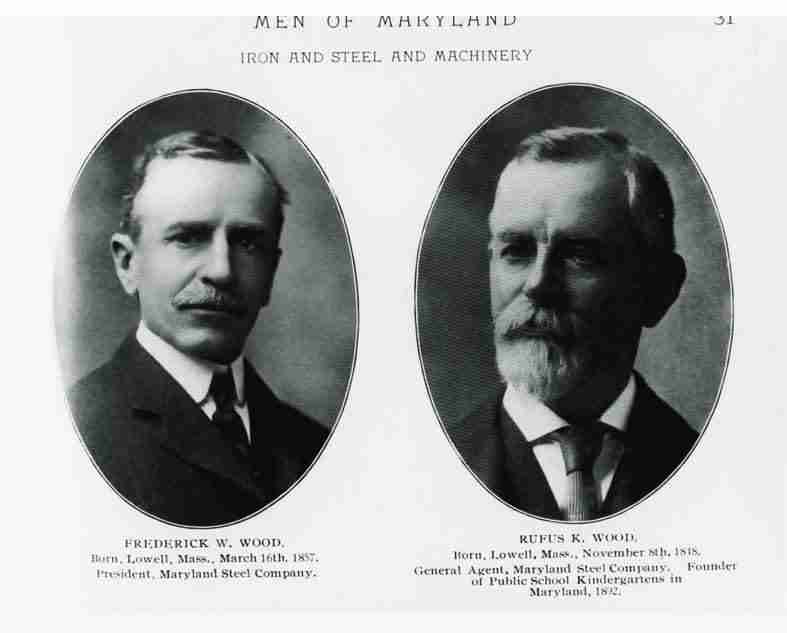

During this time in history, the Sparrows Point steel mill was owned by the Maryland Steel Company and managed by two brothers, Frederick and Rufus Wood. In his testimony, Frederick W. Wood, the president of the Maryland Steel Company, said that the cause for the explosion was unclear but that he supposed that it had been caused by water leaking into the furnace through a cracked pipe at the bosh.

According to Maryland law, any suspicious deaths at the mill were heard by an inquest jury of local citizens. Of course, almost all “local citizens” were connected to the company and the jury for this accident included a superintendent from another department and a blast-furnace foreman, among others. The jury concluded that the cause of the explosion was a mystery and that the “Maryland Steel Company [was] not accountable.”

This verdict cleared the company of any responsibility and protected them from lawsuits. Although George Braidwood’s widow filed a suit against the company for $10,000, it is likely that none of the men’s surviving loved ones were ever given any recompense.

Was the company truly innocent?

The management had known that the pipes and walls of the furnace were damaged but they did not order the men to “blow out” the furnace for some time after they discovered the damage. Instead, they waited to shut the furnace down and make the necessary repairs.

Should the company have shut down the furnace immediately after they learned about the damage? Could the time they let pass have allowed the pipes to further deteriorate and contributed to the explosion? These are questions that were not addressed at the time.

It’s worthwhile to note that the Maryland Steel Company was very rarely found guilty when its workers were injured or killed on the job. Since workers were free to take or leave a job, the law said that employees assumed the risk associated with the employment they chose. It was the workers’ job to take full responsibility for the dangers of machinery that they had very little, if any, control over. The company had almost no legal obligation for the safety of its employees.

Absent legal obligation, there was little financial incentive for the Woods to invest in safety measures. When there was a risk that the company might be held responsible, the company offered men who had been injured on the job small cash settlements or paid for their hospital bills if the men agreed to sign waivers that released the company from any liability. These bills were miniscule compared with the company’s total sales income, especially when one considers the cost of engineering safer machines and setting up safety training for employees. This pattern of not holding the steel mill responsible for workers who were injured or killed remained the norm until 1914, when the Maryland state legislature passed a workman’s compensation law that required employers to provide insurance for work-related injuries.

The steel mill started out as a dangerous place to work and remained dangerous until it closed down in 2012. Read more about this explosion and the history of Sparrows Point in Mark Reutter’s book or view more photos of Sparrows Point during this time here.

Author Bio

Clair Volkening is an English major at University of Maryland Baltimore County and an intern with the Baltimore Museum of Industry.