Andrew Morton began working at Sparrows Point in 1970 in the labor gang. A self-described “little skinny kid” who debated quitting after his first few days on the job, he spent more than 40 years at Bethlehem Steel. Morton worked in the blast furnace, the coke ovens and the 68 Hot Strip Mill. At the same time, he began taking computer classes and spending his free time studying and sketching the mill. According to Morton, he became the first Black worker at Beth Steel to hold both a union job and an outside contract when he won a contract to develop new training software for the company. He was one of the last steelworkers at the mill when it closed permanently in 2012.

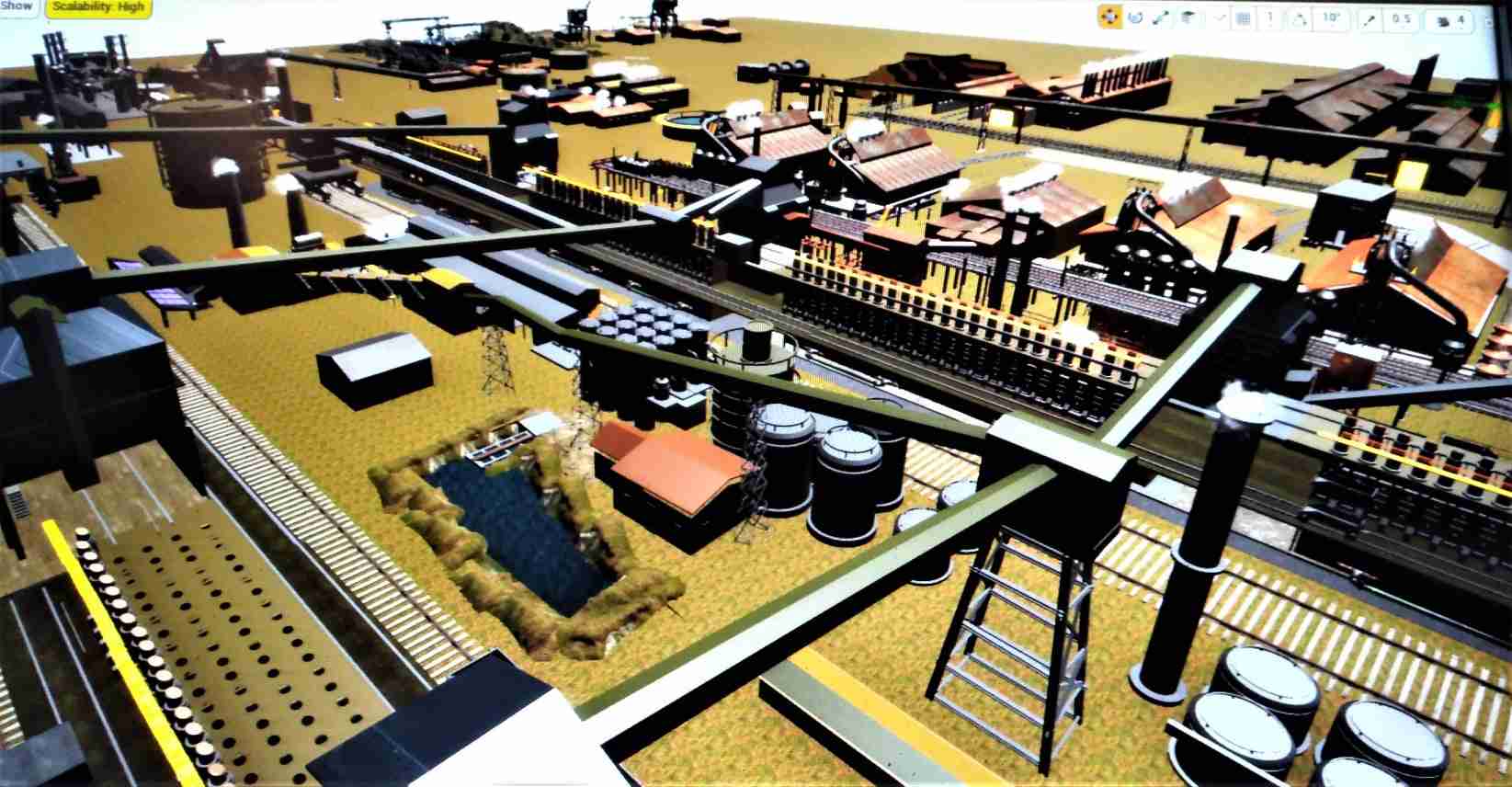

Morton is bringing the steel mill to life in the form of a virtual reality (VR) experience. He spent the past two years building over 7,000 individual pieces into an immersive, animated model of the mill. His model resembles a video game. Viewers follow a piece of steel on its journey from raw material to finished product. Though still incomplete, Morton’s VR experience helps explain the process and the staggering scale of steelmaking operations at Sparrows Point. He envisions adding a 3D scale model of the Turner Station community in addition to the mill itself–and eventually constructing virtual renderings of other historic sites in the Baltimore area.

Below are excerpts from a 2020 interview between Andrew Morton and WYPR senior producer Aaron Henkin, as part of the limited-edition podcast “Sparrows Point: an American Steel Story.” Portions of this interview have been edited for brevity.

Developing the training software

It doesn’t make sense for guys to have to spend six to eight months training on a job; something is wrong with the training practices. The training manual was written and designed by engineers. Wasn’t designed for operations, but yet still the operational people were the ones that were doing the work. Engineers couldn’t do the operational job and operational people couldn’t do the engineer’s job. I started learning all the parts of the mill – engineering, mechanical and electrical. I started sketching the mill. I would stay after work and I would sketch the mill. People thought I was crazy.

I developed a love for the mill. Sometimes I would go home thinking about the mill. If I made a mistake, I would go home and think about, what mistake did I make? How can I rectify that? It came to a point where the mill became an obsession with me. Guys didn’t realize that I fell in love with the mill. My girlfriend, she would get on me all the time, “You love that damn mill more than you love me,” but in actuality it was the truth. I enjoyed being there.

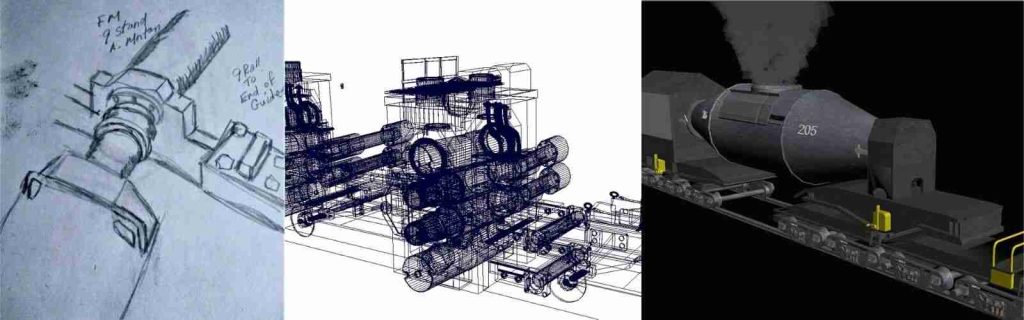

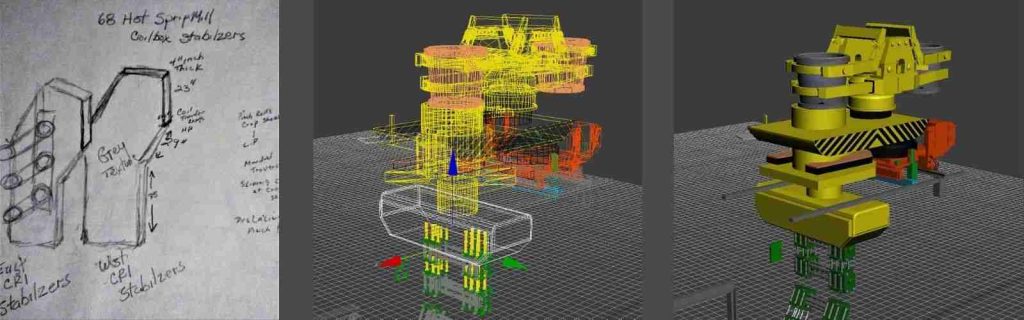

I used the software patches called LightWave, at that time it was called Imagine, and started designing parts of the mill and making them actually move. I used my knowledge of C++ and C to create a software training package. The engineers wouldn’t listen to me at first, but they started understanding that I knew what they were talking about. They started talking to me every day about the mill, and I started teaching them about the operations of the mill and how the mill actually worked and moved and calibrated. We started interchanging knowledge. They helped me tremendously with designing the software.

[Morton requested a meeting with management, competing against two major companies for the training software contract.] I said, “Look, if I have a product here that can benefit this mill and allow us to have a better product to give to our customers, and better trained people working here, don’t deny me because of the color of my skin.” They thought about what I said. By the time I got home, they called and said, “We want your software.”They paid me as a special activities and outside consultant to help them design the training packages for the furnace. I became the first African American in the history of Bethlehem Steel to be an hourly paid union person and to be paid the same time as an outside contractor, designing software.

On the company’s failure to change

I started realizing that the days of the blast furnaces were numbered. I told the guys, “These furnaces are not going to be here forever,” and the older guys were hard to change. They clung to the idea that Maryland couldn’t survive without Bethlehem Steel and that was a fantasy. Well, they clung to that fantasy to the end.

When I first started, we made everything, we did everything. Everything came through Bethlehem. Well, the world caught up to us, and we did not change. We thought we were invincible. We thought Maryland couldn’t survive without Bethlehem Steel. That was our downfall. Nobody or no person, no plant, no company can be an entity unto themselves. They have to evolve and they have to change. If a company refuses to change, if their employees refuse to change and evolve with the technology that we have, the company will fail, and that’s what we did.

His take on technology

I tell people don’t be afraid of technology. Technology is here forever. It’s not going anywhere. It’s only going to get better. I don’t believe that old cliché, “You’re too old to learn new tricks.” I believe that every day that you are gifted, that you are alive, you could learn something. Regardless of all the machinery and all the technology, it still needs human influence, and if you do not have the human influence in there, you do not have the skill trained people in there, you can have all the technology in the world, you’re going to fail. They have to work hand in hand.

His vision for the VR project

I’m going to create a VR of the whole plant where you can actually walk through the mill because this mill is not going to be here forever, and when it’s gone, we want to keep the legacy of the Bethlehem Steel – a shrine to the men and women that worked there before me and with me. I want to keep their legacy going. That’s what drives me to keep doing this. When people ask, “What was Bethlehem Steel really like?,” they’ll have an exact replica of the mill that they can walk through and interact with.