Compiled by Deb Weiner

Bob Casey had a career in steelmaking before leaving Sparrows Point to become a museum curator. Starting with a stint as an intern here at the BMI, he eventually retired as Curator of Transportation at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, MI. Recently he donated four items from his time at Sparrows Point to the BMI. Below, he recalls life as a Bethlehem Steel “Looper.”

I took a job with Bethlehem Steel after graduating from Rose Polytechnic Institute (now called Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology) in Terre Haute, Indiana, with a degree in mechanical engineering. The year was 1968 and job offers were plentiful. I think I had nine, which was about average in my senior class. I narrowed my choices to two: Pontiac Motor Division of General Motors, and Bethlehem Steel.

Bethlehem had a management training program called the “Loop Course,” because trainees spent time making a “loop” around all operations of the plant, learning about each. After graduation my new wife and I went to Bethlehem, PA to begin the course. We “Loopers” spent a month touring the plant, observing every phase of the steelmaking operation. We were tested weekly on what we had observed, and had homework. We also listened to talks by general managers from Bethlehem’s other plants—Lackawanna, NY; Johnstown and Steelton, PA; Burns Harbor, IN; Sparrows Point; plus the shipyard and steel fabrication operations.

Near the end of our month in Bethlehem we Loopers were asked to choose which plant we wanted to go to. My wife and I settled on Sparrows Point. As the largest plant it had a variety of opportunities, and Baltimore seemed like an interesting place for two people who grew up in the Midwest. Like most of my fellow Loopers, I got my first choice.

When we arrived in Baltimore, Bethlehem put us up in a Holiday Inn on Pulaski Highway. It was not a good neighborhood. Sherry’s Show Bar topless club was down the street, and one of the Loopers had his car broken into in the Holiday Inn parking lot. We took everything visible out of our car and hauled it up to our room. My poor wife was stuck in the room all day until we could find permanent housing. Bethlehem gave us a couple afternoons off to find a place and we ended up renting an apartment in Middle River. Three other Loopers were in the same apartment complex.

Sparrows Point ran its own shorter version of the Loop Course. We toured the plant and heard from each department superintendent. When asked to choose where we preferred to work, I chose the Fuel Department, and fortunately they chose me back. The Fuel Department was responsible for the measurement and control of all the fuels—gaseous, liquid, and solid—burned in the plant. By extension it was responsible for all automatic control systems, even if they did not involve burning fuels in furnaces.

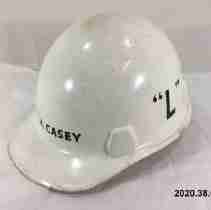

This miniature version of the “Flaming L” blast furnace was built by Bob Casey’s coworkers and given to him as a gift upon his departure from the company in 1980. Bob, pictured on the right, said: “I have kept the little “L” for the last 41 years because it reminds me of an important time in my life and of the good people I worked with.”

The Fuel Department had shops throughout the mill: coke ovens; blast furnaces; steelmaking (open hearth and basic oxygen furnace); soaking pits, blooming mills, and plate mills; rod, wire, and pipe mills; and hot strip, sheet, tin, and cold strip mills. Each area was headed by a combustion engineer, with one or more assistant combustion engineers under them. The Department conducted its own version of the Loop Course as well. I spent a month in each of the areas. My most memorable month was working in the dust testing lab. Meeting air quality requirements meant testing stack effluent for particulate matter. To do that we had to climb ladders to platforms mounted on the sides of smokestacks, and insert probes into the stacks to collect dust samples. While I was not truly afraid of heights, neither was I particularly comfortable. I got over it.

My first major assignment was the construction of a new boiler house, officially known as B Street Steam Station. I also did a stint in the basic oxygen furnace before being assigned to the construction of the new “L” blast furnace and being promoted to assistant combustion engineer in 1976. I did engineering work on the automatic control systems, set up the fuel shop for “L” furnace, and trained the crew of instrument mechanics. My group was the first in the Fuel Department to work shift work. The furnace blew in in November 1978. In May 1979 I was promoted to combustion engineer of the blast furnaces.

The “L” project was an excellent experience. I worked with good people and we built a world-class facility. I also got two trips to Europe. To get the best technology possible, we chose suppliers from all over the world. I went to Switzerland to learn about the control system for the Sulzer Brothers turbo blowers that supplied the blast to the furnace, and to Holland to learn about the stoves we bought from Dutch steelmaker Hoogovens. The furnace startup went smoothly and we soon made our rated output of 8,000 tons of iron per day. In May 1995, “L” set a North American production record of 305,904 tons, an average of 9,868 tons per day. I watched internet videos of the destruction of the furnace in January 2015 with great sadness.