by Ken Jones

In the early 1980s the U.S. shipbuilding industry was in a slump. Construction of new merchant ships was steadily declining. According to the American Council on Shipbuilding, in 1975 the industry produced 75 commercial ships, in 1979 it produced 22, and by 1985 it produced only five—a staggering 75% decrease in production over ten years. A major factor in this decline was the elimination of the Construction Differential Subsidy (CDS) provided by the United States Government in 1981. The CDS covered up to 50 percent of the additional cost to build ships in a U.S. shipyard instead of a foreign yard. Without these subsidies the industry was not able to compete with government-supported foreign shipyards.

The Bethlehem Steel yards in Baltimore were feeling the pinch. The Baltimore yards on Key Highway were up for sale and would close by the end of 1982. Sparrows Point was finishing up construction of five offshore drilling rigs and would be without work by September of that year. The Sparrows Point Shipyard workforce, recently 3,000 strong, was only employing 1,800 workers. The other 1,200 had been laid off.

The only contracts being let were from the U.S. Navy. In early 1982 a contract was coming up to build a floating dry dock to service the nuclear submarine fleet stationed in San Diego. Leadership of the Bethlehem Shipyard and the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers felt they had a good chance of winning this contract since they had built one of the same design for the Navy in 1979 to serve the submarine base in Groton, Connecticut.

In an attempt to win this contract without competitive bidding, Bethlehem Steel, the union, and Maryland’s congressional delegation invited Secretary of the Navy John F. Lehman, Jr. to tour the Sparrows Point Shipyard.

According to Baltimore Sun reports of the visit, the majority of the Maryland congressional delegation attended the event. Company managers, union representatives, and local elected officials were also in attendance. Secretary Lehman was non-committal on the contract award but encouraged the congressional delegation to support the Reagan Administration’s defense budget.

In a bold move, Bethlehem decided to submit an unsolicited proposal to the Navy. Details of the proposal were leaked to the media. Exposure of the unsolicited proposal seemingly compelled the Navy to open a competitive bidding process for the drydock. Ultimately, the contract was awarded to the Todd Pacific Shipyards in Seattle, Washington. Cost and proximity won out over experience.

Secretary of the Navy John F. Lehman, Jr. responds to a reporter’s questions while surrounded by members of Maryland’s congressional delegation.

Although the yard was not awarded the floating drydock contract, the visit may have had influence on the award of several other contracts over the next few years.

One of those projects was the conversion of three roll-on/roll off ships (RO/ROs) converted to Maritime Prepositioning Ships for the U.S. Navy’s Sealift Command. The yard also won a contract to build two oceanographic survey ships for the U.S. Navy: the USNS Maury and USNS Tanner were the last two ships constructed at Sparrows Point.

The Sparrows Point shipyard was sold in 1997 to Baltimore Marine Industries Inc., ending Bethlehem’s involvement in shipbuilding. Baltimore Marine Industries won two U.S. Navy contracts for new ship construction and dismantling of older tonnage. Although the company was selected to build a fleet of deluxe cruise ships, the cruise line was never able to secure financing. With no orders on the horizon and no work aside from the two modest Navy contracts, Baltimore Marine Industries collapsed in bankruptcy in 2003. In 2004 it was reorganized, under new ownership as the Sparrows Point Shipyard and Industrial Complex. That operation failed as well, essentially bringing to a close the story of Baltimore’s shipbuilding legacy.

These oil rigs under construction in the flexible building basin were sustaining current employment levels.

Editor’s Note

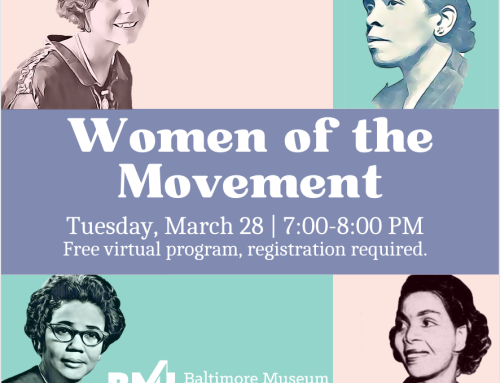

The BMI’s Bethlehem Steel ship plans collection includes material from five shipyards in the Greater Port of Baltimore and represents the experiences of thousands of Baltimore workers from 1896 to 1985. After five years of deep processing, we are excited and proud to announce that more than 25,000 ship plans are now available for research. Discover Baltimore’s immense shipbuilding achievement and help us uncover a world of largely unexplored material and scholarship: Liberty ships, Victory ships, cargo ships, military and naval vessels, Coast Guard cutters, lifeboats, tugboats, barges, dredges, tankers, and private vessels are represented. Navigate the collection by contacting archives@thebmi.org.

A significant artifact from the Bethlehem shipyards is the BMI’s recently restored 1942 era Clyde Model 17 DE 90 whirley crane. This crane was used in the Fairfield yard in the 1940s and later moved to the upper yard on Key Highway. The crane sat on Pier 3 at Key Highway and was used throughout the 1940s and into the 1980s. After the closing of the yard in 1982, it was donated to the museum and installed on our campus in 1991.

Author Bio

Ken Jones is a retired marketing communications executive now volunteering in the museum’s collections and archives department.