by Ken Jones

As mentioned in my previous post I have been processing and cataloging the Museum’s Bethlehem Steel collection. As I did my work, I found myself reading the materials or closely looking at the photos I was processing. I became fascinated by Bethlehem’s collection of shipyards in Baltimore – Sparrows Point, the Baltimore Yards and Fairfield – and the contributions that they made to local and global commerce as well as the major role they played in national defense.

In the first post we looked at the Baltimore Yards, in this post we’re going to take a look at the Fairfield Yard.

Illustrating the massive building effort at Fairfield, in the foreground three Liberty ships are at the outfitting pier while the slipways are full of ships being built and in the background additional slipways are under construction.

The origins of the Fairfield yard can be found in the United States Maritime Commission’s Emergency Shipbuilding Program of January 1941. The commission wanted to build a commercial fleet to replace the dozens of vessels that were being sunk each week by German U-boats.

Since Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point and Key Highway shipyards were already operating at full capacity, the company acquired the Union Shipbuilding Company, a small operation in south Baltimore that had not built a vessel since World War I. To improve workflow and material handling at the site, Bethlehem also took over an idled Pullman car fabricating shop in nearby Curtis Bay and linked it to the shipyard with two-and-a-half miles of railroad track.

The complex was spread across 136 acres. Fairfield’s 13 slipways (later expanded to 16) were serviced by 75 cranes, 10 locomotives, and more than 200 flatcars. The yard employed a modular construction concept—the components of the ship were built at the fabricating shop and then transported to the slipways for staging and final assembly. This proved to be extremely efficient and was eventually adopted by many other shipyards. The concept is still practiced today.

With those foundations in place the Fairfield yard was one of several new emergency shipyards tasked with constructing the “Liberty Fleet.”

Work on building the Fairfield yard began in February 1941. Even while the yard was being constructed the first keel was being laid. On “Liberty Fleet Day,” September 27, 1941, thousands journeyed to Fairfield to witness and celebrate the launch of the S.S. Patrick Henry, the first Liberty ship built in the United States.

According to a Baltimore Sun account the celebration went well beyond Baltimore, “At the hour of Patrick Henry’s launching, American merchant ships, wherever they might be – if conditions permitted – were dressed in their brightest bunting and blew a salute blast on their whistles to the new vessel. Shipyards whistles all over America did the same, and American Naval ships as well.”

That was the beginning of the Fairfield yard making its mark on history. Between 1941 and 1945, the Fairfield yard built a total of 384 Liberty ships, more than any other shipyard in the nation. The yard also built 94 Victory ships—the larger, faster cousin to the Liberty ships—and 45 LSTs (Landing Ship-Tank), making it one of America’s most productive wartime shipyards. The museum’s Joseph Abel tells a more complete story of this time period in his post.

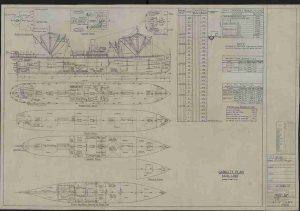

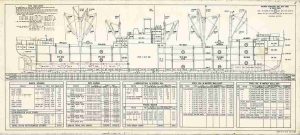

The shipyard pictured in October 1941. It is likely that one the these cranes was to eventually find a home at the BMI.

The BMI holds significant artifacts from the Fairfield Yard. One is our recently restored 1942 era Clyde Model 17 DE 90 whirley crane. This crane was used in the Fairfield yard in the 1940s and later moved to the upper yard on Key Highway. The crane sat on Pier 3 at Key Highway and was used throughout the 1940s and into the 1980s. After the closing of that yard in 1982, it was donated to the museum and installed on our campus in 1991. In addition, the BMI has a collection are more than 25,000 ship plan drawings from all of the yards, including the Liberty and Victory ships built at Fairfield.

Shipbuilding operation ended at Fairfield in 1945. After the war the yard functioned as a scrapping operation providing needed scrap for the steel making operations at Sparrows Point. It also became home to Bethlehem’s Buffalo Tank division, and was used as a tanker cleaning facility for tankers to be butterworthed and made gas-free before they entered the Baltimore Yards for repair.

Returning Fairfield to its maritime roots, today it is the home of Maritime Applied Physics Corporation, a company that designs and builds advanced technology systems and water vessels–including Baltimore’s new water taxis. It may also become the home of the SS John Brown, one of only two remaining Liberty Ships.

Editor’s Note

Interested in learning more about ship plans? The BMI’s Bethlehem Steel ship plans collection includes material from five shipyards in the Greater Port of Baltimore and represents the experiences of thousands of Baltimore workers from 1896 to 1985. After five years of deep processing, we are excited and proud to announce that over 25,000 ship plans are now available for research. Discover Baltimore’s immense shipbuilding achievement and help us uncover a world of largely unexplored material and scholarship: liberty ships, victory ships, cargo ships, military and naval vessels, coast guard cutters, lifeboats, tugboats, barges, dredges, tankers, and private vessels are represented. Navigate the collection by contacting archives@thebmi.org

Author bio

Ken Jones is a retired marketing communications executive now volunteering in our collections and archives department.