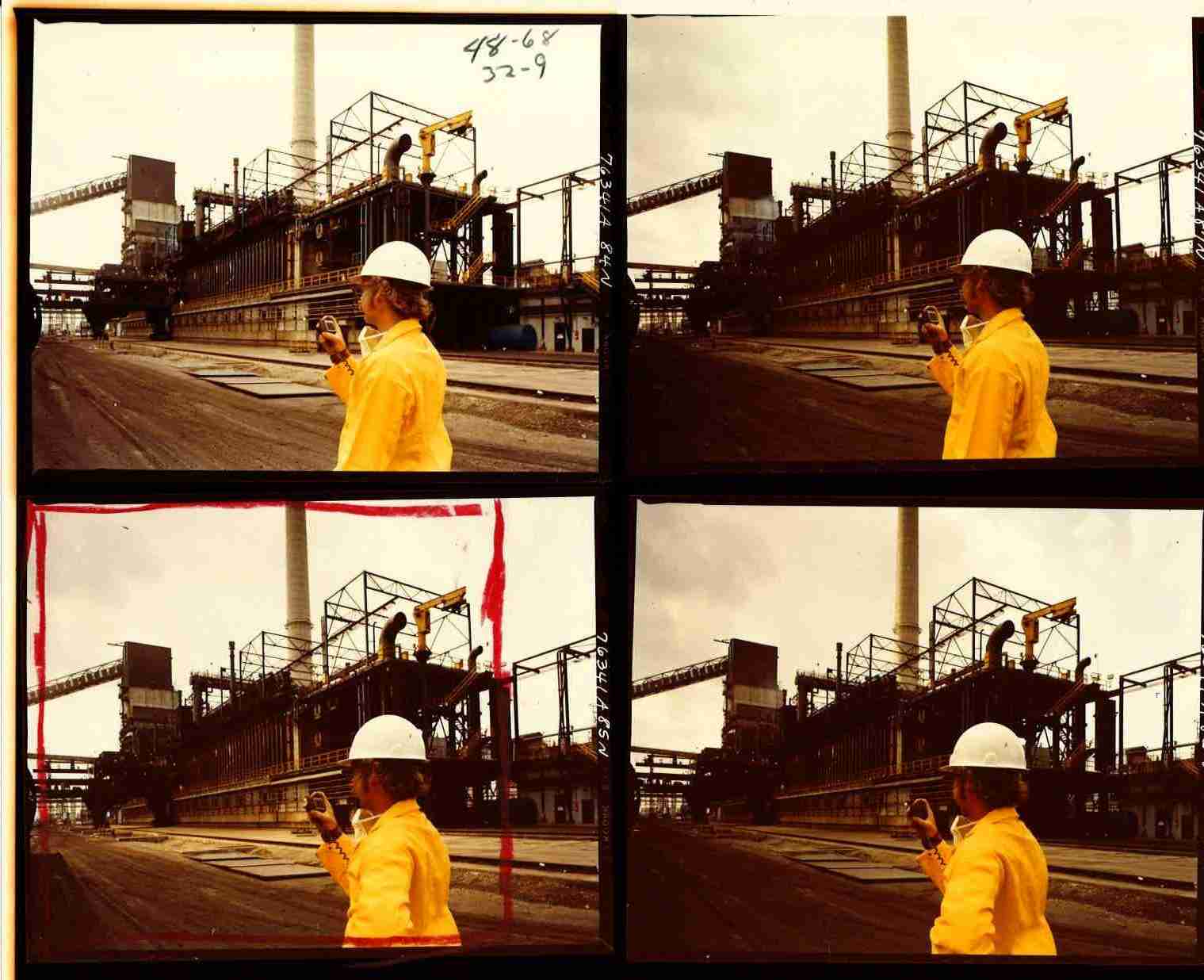

Gordon Davis at the Sparrows Point coke ovens. Gordon worked at Bethlehem Steel for almost 40 years. Photo courtesy of Gordon Davis.

by Joseph Abel

“You had to dance with the fire a little bit.”

In our last post, Deb Weiner recalled highlights from her interview with Roy Hoover, a longtime crane operator in the Bethlehem Steel shipyards. This week, we get a view from the ground with the reminiscences of Gordon Davis, a jack-of-all-trades who worked many different jobs at Sparrows Point from 1974 to 2012.

Davis was born and raised in east Baltimore just north of Patterson Park. Like many others, his father also worked at Bethlehem, first as a millwright and later as a foreman in the pipe mill. Two weeks after graduating from Patterson High School, Davis was presented with a choice. “I had two envelopes in my hand,” he recalled. “One from General Motors [Broening Highway plant], and one from Bethlehem Steel. I decided the right hand rules, and I had [the] Bethlehem Steel paper in my hand and said, ‘Okay, I’m going to go here. Dad’s working there, I’ll get a ride with Dad.'” When Davis learned that his new job was in the coke ovens, his father’s response was prophetic: “‘You’re going to be in for a surprise.'”

A load of newly processed coke on its way to be quenched at the “A” Coke Oven Battery, c. 1982, from the BMI’s Bethlehem Steel Collection.

Even at a place known for difficult work, the Bethlehem Steel coke ovens were notoriously unpleasant. A type of metallurgical fuel produced by heating coal in tightly sealed ovens, coke is an essential ingredient of modern steelmaking. Davis vividly recalled the sights and smells of his first day on the job: “[Dad] was right, I was not ready for the visual concept of what was going on there…It was a rather gray, dark day when I started there, and the only light I saw was the flames licking the top of the batteries. Just the odors, some pungent, some burning, and things that smelt like moth balls. Come to find out later [that] was actually one of our byproducts, naphtha. Sulfur was heavy in the air, and there was like a silvery dust floating everywhere.”

Davis was part of a labor gang whose work involved mixing and handling a special type of black mud used to seal the doors of the coke ovens. “It was Neanderthal,” Davis recalled. “If you worked the mud mill, it either broke your back or made your back because it was heavy and a lot of lifting.” Not surprisingly, the coke ovens were extremely dirty. This made laborers such as Davis easy to spot. “You knew you were in the mud mill because you used to look like you had mascara on both eyes,” he remembered. “You’d be away for two days…[and] you would still be coughing up the black dust and it’d be seeping out of your eyes and blowing out your nose.”

Cooperation was important in such a grueling environment and everyone was expected to pitch in. Those who slacked off often found themselves having to do more than their share, a fact Davis says he learned the hard way: “A normal run of seven ovens would be one and half wheelbarrows, [but] I’m getting seven wheelbarrows off of each run now. I said, ‘Okay, I got to go learn how to mud tops or bottoms…they want a break. I’m going to help them.'”

Charging car operator working on top of the “A” Coke Oven Battery, c. 1982. The lidman can be seen in the background. From the BMI’s Bethlehem Steel Collection.

After several years in the mud mill, Davis was promoted to the position of lidman. Situated on the top deck of the multistoried coke ovens, his job was to help transfer raw coal into the 2,000-degree inferno below by removing and replacing the heavy steel lids used to seal the charging ports. Working as lidman presented new hazards, including geysers of flame and toxic gases: “You would pop the lid on the stand pipe…based on the direction of wind blowing because when you pulled the lids off, the fire is coming at you. You had to dance with the fire a little bit. I’m not talking a foot fire, sometimes them flames would be as high as me, five, six feet. For the love of God, don’t pull the wrong oven, what they call a green oven that’s not ready to be pulled. Unfortunately, I did that one night and thank God there was a helper there…I got a wind of green gas and it felt like a heart attack, and I hit the ground. When you hit the ground on the top deck, you’re going to be burning. [The helper] pulled me off, got me to the dispensary, and I was forced to drink this white mixture…to break up all the gas in my chest so it wouldn’t poison me. That worked, and I was out for about two days on that.”

Sometime later, Davis narrowly escaped a deadly accident on the top deck when his leg got caught between the rails for the oven’s massive larry car. “I’m here because of [Melvin Blount, turn foreman]. He saved my life,” Davis recalled. “Melvin came up the steps and I’m yelling at that time…he jumps, pulls the lanyard, and the larry car drifts within about six feet of me dead. It took them 20 minutes to get me out of that position, which tells me I’d have been sheared in half.”

In spite of these dangers—or perhaps because of them—Davis enjoyed his years at Bethlehem Steel. “I got to say, having the opportunity to work with men that were allowed to be men down there, that was the thing,” Davis remembered fondly. “We had a good thing going with that.”

Author Bio:

Joseph Abel is the BMI’s Research Historian and acting curator.