And it happened right here in Baltimore

The Mini-Mariner is a ⅜ scale model of a flying boat bomber used by the U.S. Navy. Constructed by Baltimore’s Glenn L. Martin Company in 1937, this prototype helped the company’s designers identify improvements that went into the full-scale PBM Mariners it later produced.

Today, this ⅜ scale model of the Martin Mariner patrol bomber, the Mini- Mariner, hangs in the BMI’s Decker Gallery, fascinating museum guests. It is one of the museum’s most popular artifacts on permanent display.

We hope you enjoy this quintessential Baltimore story. Turn the page to read more about the Mini-Mariner model, pilot, and restoration. Thank you again

for your support—which makes it possible for the BMI to preserve the documents, photographs, and artifacts that reveal stories like these.

Martin Model 162A Tadpole Clipper “Mini-Mariner” on loan from the Smithsonian Institution, National Air and Space Museum collection, inventory # A19530086000

The Model

In the first decades of the 20th century, when airplanes were a new and rapidly changing technology, flying boats were especially important. The distance an airplane could fly without stopping

or refueling was limited by the size and power of engines, so it was important to have a plane that could set down on water (or, sometimes, either land or water). The Glenn L. Martin Company, located in Middle River, Maryland, just northeast of Baltimore, was a leading designer and manufacturer of flying boats in their 1930s heyday. To the public, the most famous and spectacular of the Martin flying boats were the “Clippers,” built for and flown by Pan American Airways for its transpacific route. But Martin’s most important client was the U.S. Navy, and from the 1920s into the 1950s the company constructed several important craft for a range of naval uses. One of the most versatile of these craft was the Mariner, which the Navy used largely for coastal patrols. It was equipped as a bomber as well as an observation plane and so had demanding performance requirements. To assist in meeting these, the Martin engineers constructed a unique model, dubbed the Mini-Mariner, which first appeared at the end of 1937. All new aircraft designs relied on models (at least, before computers) to determine how they would behave in the air and, in the case of flying boats, on the water. For the Mariner, Martin engineers figured they would get much more data than usual if the model were piloted.

This is why the Mini-Mariner was built at the unique scale of 3/8—it was the smallest that could be built and still accommodate a pilot, an operating engine, and sufficient fuel for flight. The full-scale Mariner was a large seaplane with two sizable engines, one on each wing. The model had room only for one engine, which was mounted in the center of the hull and connected to the propellers with pulleys and belts. The pilot was in the front seat, but behind him, where an engineer would sit in the final plane, were tanks for the fuel. The belt-drive turned out to be very unreliable, so the model spent very little time in the air. A bit more was learned from seeing how it behaved in the water, which could be particularly hard to predict in seaplane design.

Over about six months, until the middle of 1938, test pilots for Martin flew the model several times, until engineers figured they had learned all they could from it. For about 15 years, the Mini-Mariner hung in an assembly building at Middle River, until in 1953 it was taken down and donated to the Smithsonian Institution.

Cable Machine

Transcontinental communications

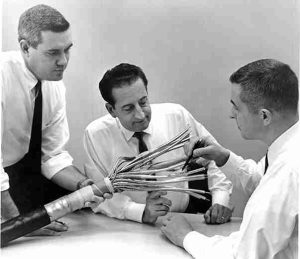

Baltimore native J. Carroll Tulloss joined Western Electric in 1938, about 60 years after Alexander Graham Bell received a patent for the telephone. In the intervening de- cades, Western Electric won the contract to manufacture Bell’s telephone and AT&T was formed to build and operate a long-distance telephone network. When the two companies merged, Western Electric became the exclusive manufacturer of all components for the company’s network.

Building a transcontinental tele- phone network was one of AT&T’s top priorities. To do so, it needed to figure out a way to overcome signal weakening over long distances. The technological breakthrough came with the development by Dr. Lee DeForest of the audion, a three-element vacuum tube that could send radio waves more effectively and amplify them as well. AT&T purchased the audion patent from DeForest and applied the concept to the development of a high-vacuum tube for amplifying sound in telephone cables. The buildout of the transcontinental network could now move forward.

As demand for more telephone lines and equipment grew in the early decades of the twentieth century, AT&T rose to meet the challenge. The first transcontinental telephone calls were transmitted over four copper wires held up by 130,000 wooden poles. The grow- ing demand for long-distance telephone service required a more efficient way to transmit the signal. The search for a broader bandwidth, higher capacity transmission medium was on.

Western Electric employee splicing cable

It’s all about the cable

In 1929, scientists at Bell Laboratories, AT&T’s research and development subsidiary, invented and patented a high-capacity coaxial cable. By 1936, they had developed a semi-commercial coax cable system with one tube capable of carrying 240 conversations. To manufacture the improved cable, AT&T turned to Western Electric Baltimore Works. Bell Labs continually improved the system.

By 1948, more than 5,000 miles of first-generation coax cable—the “L” carrier system—were in service, providing telephone circuits and television networking facilities up and down the East Coast and west to Chicago and St. Louis. Based on the success of the system, AT&T committed to building out a nationwide coax system for telephone circuits, television networking, and national defense communications. As Bell Labs continued to develop higher capacity coax cable, it looked to the Western Electric Baltimore Works to develop the means to manufacture it.

Carroll Tulloss and two engineers with cable